August 21, 2020

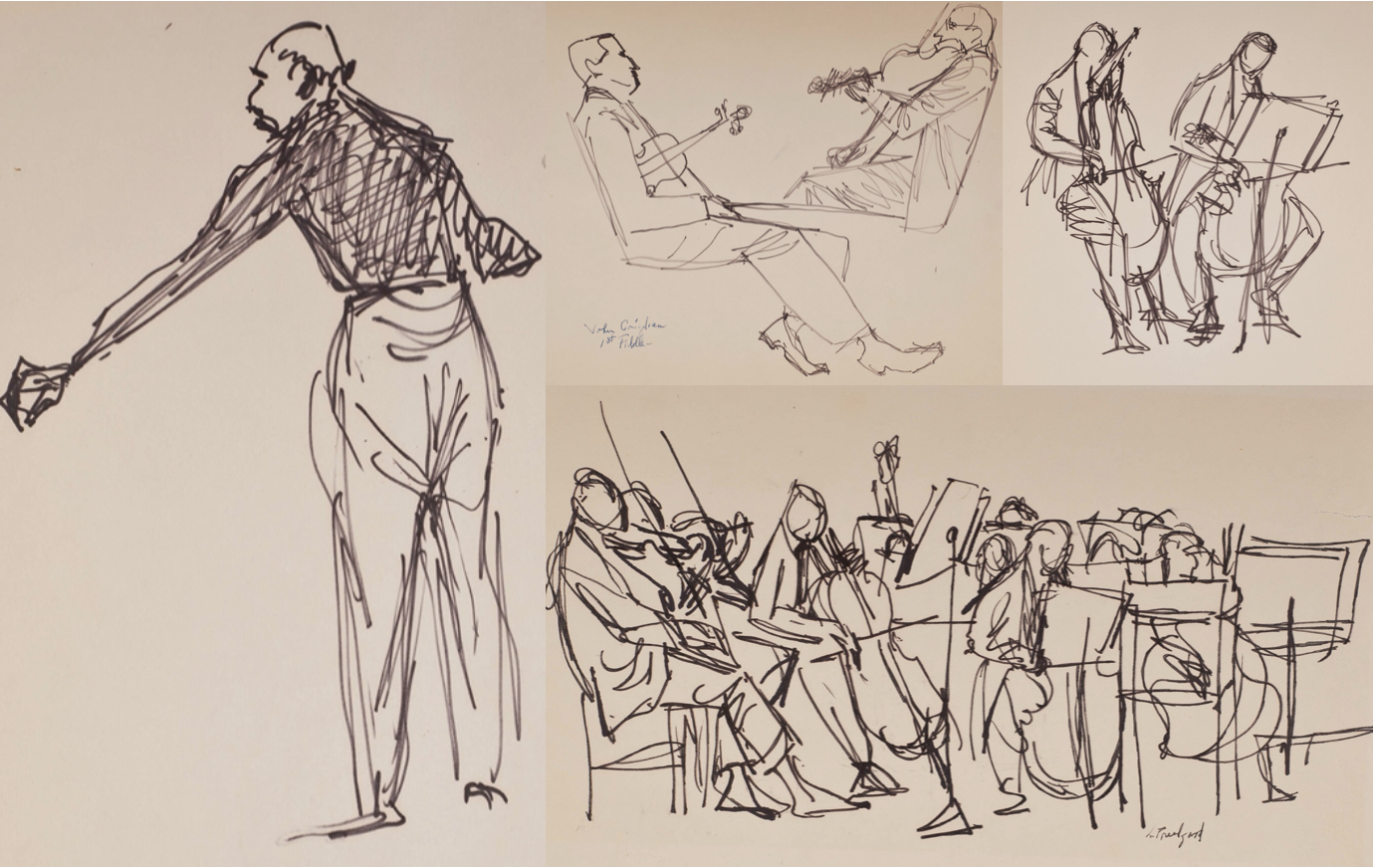

These drawings by Lillian Freedgood, done in the late 1950s, portray members of the Philharmonic in rehearsal. Freedgood was a printmaker, painter, and sculptor. Check out the rest of the series here.

In support of our audience, researchers, and online community of music lovers during the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic, the archivists posted a #dailydocument for those who wanted to dive deeper into the Digital Archives collections. While it was heartbreaking not to be able to share music in person, there was — and is — so much to learn from the history of this great orchestra.

These drawings by Lillian Freedgood, done in the late 1950s, portray members of the Philharmonic in rehearsal. Freedgood was a printmaker, painter, and sculptor. Check out the rest of the series here.

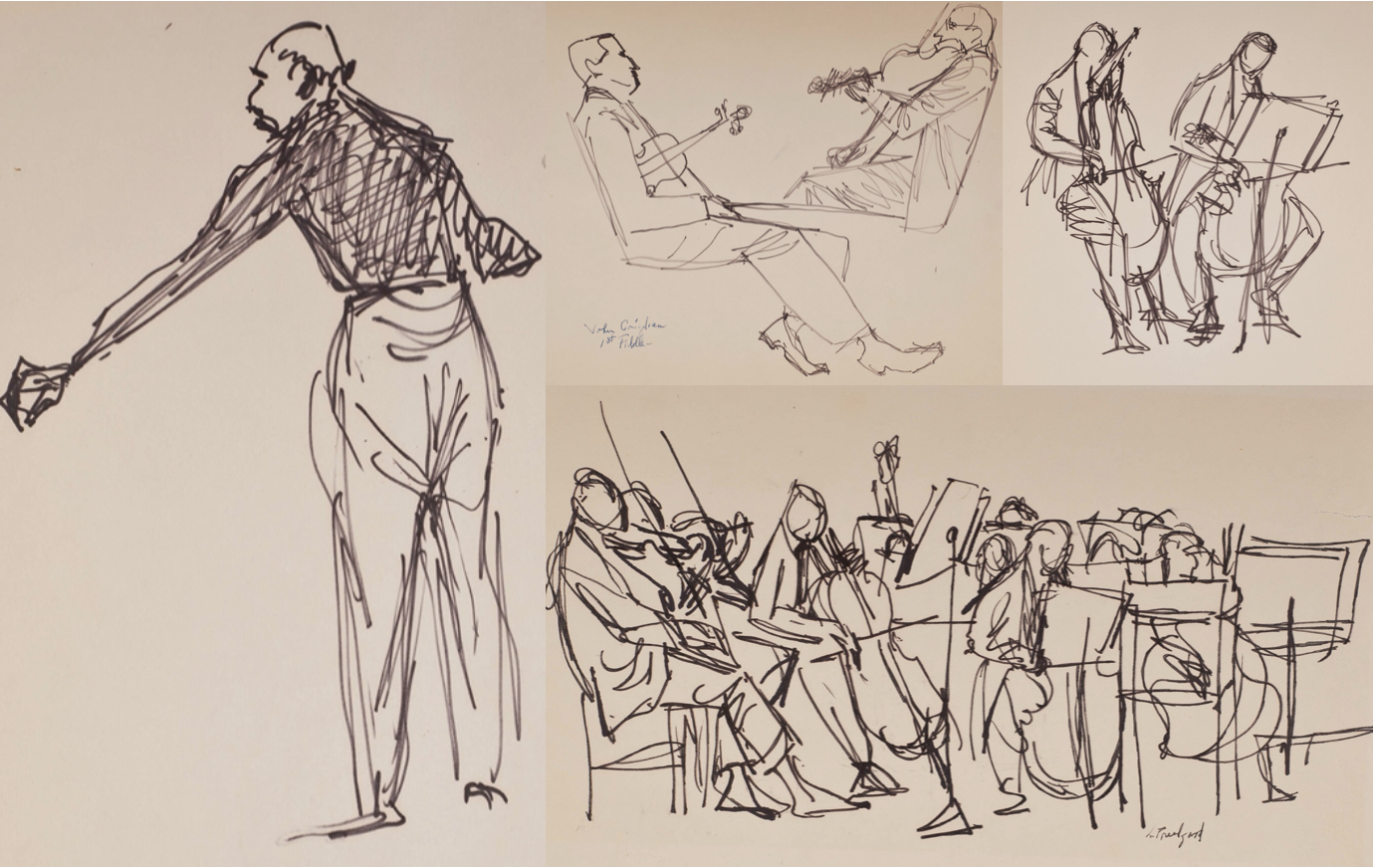

Throughout the 1950s Marion Rous, the former director of Juilliard’s pre-college program, ran a lecture series at Carnegie Hall called Philharmonic Forecasts. These talks worked as exposition to the Philharmonic’s weekend concerts and broadcasts. Rous, who led these talks, was herself an accomplished pianist. This flyer advertised the talks — Fridays at 11 a.m., $2.40 admission — for the 1951–52 season. Browse Philharmonic Forecasts material, including flyers and correspondence, in the Digital Archives

William Bell was one of the most notable tuba players in America in the first half of the 20th century. At age 18 he joined John Phillip Sousa’s band, and three years later he became the principal tuba of the Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra. In 1937 at age 34, Bell was handpicked by Arturo Toscanini for the NBC Symphony Orchestra. In 1943 he became the principal tuba player for the New York Philharmonic. Bassoonist Leonard Sharrow said that Bell “changed the whole character of the tuba. It was no longer an um-pah. It was a voice, a musical instrument. It was something beautiful to listen to.”

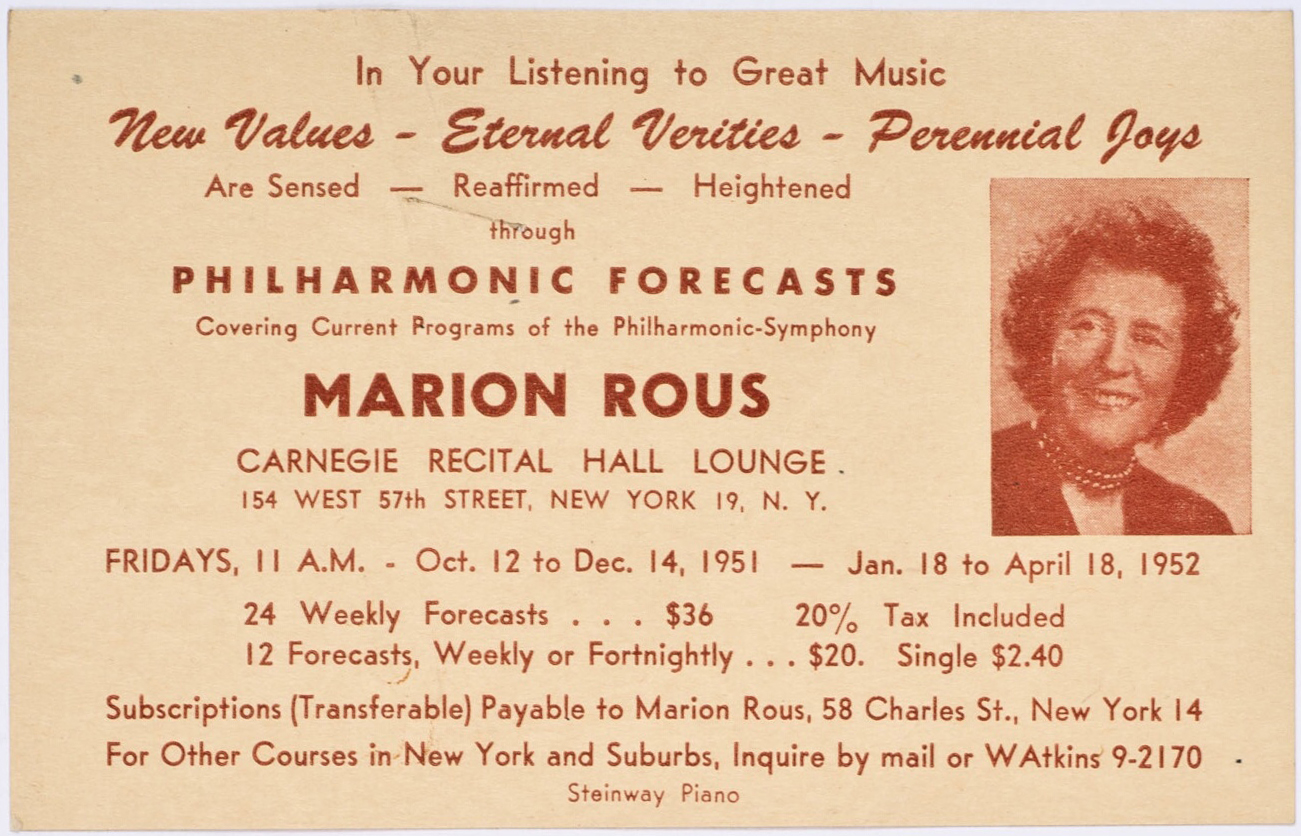

Here is a Japan Air Lines memento from 1961 on the New York Philharmonic’s tour to Japan, Alaska, Canada, and the Southern U.S. This certificate was given to Philharmonic violist David Kates on April 23, the “Day that Never Dawned.” The flight departed Vancouver at 2 a.m. on April 23, stopped for an hour in Anchorage, and arrived in Tokyo the morning of the 24th. It was the Philharmonic’s first trip to East Asia.

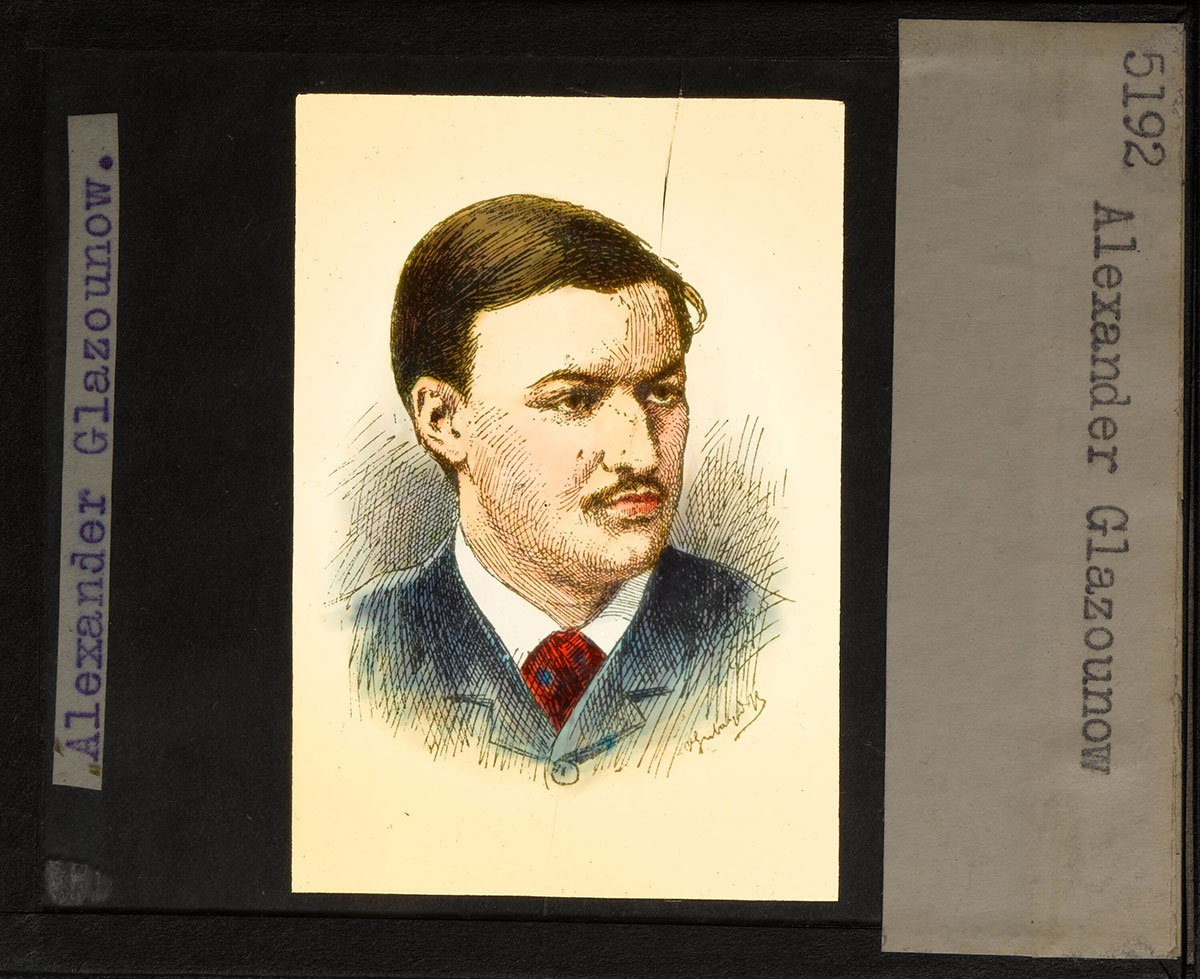

Alexander Glazunov, born this month in 1865, was a composer during the late Russian Romantic period. Some of his most popular pieces are his ballets, The Seasons and Raymonda, along with his Violin Concerto and Saxophone Concerto. Glazunov also served as the music director of the Saint Petersburg Conservatory from 1905 to 1928. Many people considered his pieces old-fashioned, and were even surprised at the announcement of his death in 1936 that he had still been alive. Glazunov’s legacy remains though, and his music is still greatly enjoyed today.

Here Glazunov is pictured on a glass lantern slide, collected by the founder of the Philharmonic's Young People's Concerts, Ernest Schelling, which were used to illustrate those concerts through the 1940s. Browse the Schelling Collection here.

In 1936 the Chalif Dancers were featured at a New York Philharmonic Young People's Concert. These dancers were from the school started and taught by the Russian Louis Harvy Chalif, whose New York school was one of the first to instruct dance teachers. He offered workshops around the country and taught classes that helped introduce ballet instruction to American children. This performance, conducted by Ernest Schelling, gave Chalif's students a chance to introduce ballet to the young audience members.

Elisabeth Rethberg, German soprano, was considered one of the greats of the early- to mid-1900s. Her first performance with the New York Symphony (an orchestra that merged with the Philharmonic in 1928) was on November 22, 1923 with a Beethoven Cycle. She would go on to perform 28 times with the New York Symphony and New York Philharmonic. She autographed this headshot to a fan and accompanist: Louis Sherman, second violinist in the Philharmonic.

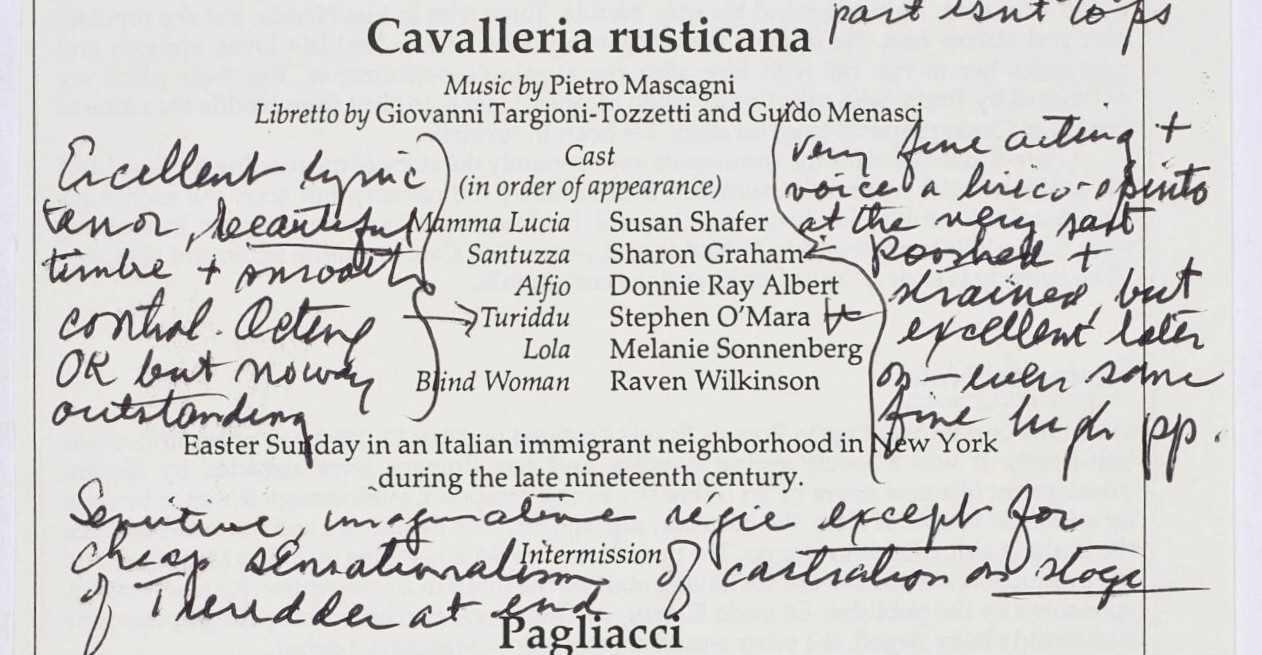

Pietro Mascagni was an influential Italian composer who ushered in the gritty yet beautiful age of verismo (real-life) opera. Audiences of the Philharmonic have been frequently moved by performances of his first, most famous production: Cavalleria Rusticana, whose gorgeous intermezzo appears as an encore in concert halls the world over. Here's a program of a 1991 New York City Opera performance found in the Archives, notated with handwritten commentary by critic and musicologist Edward Downes.

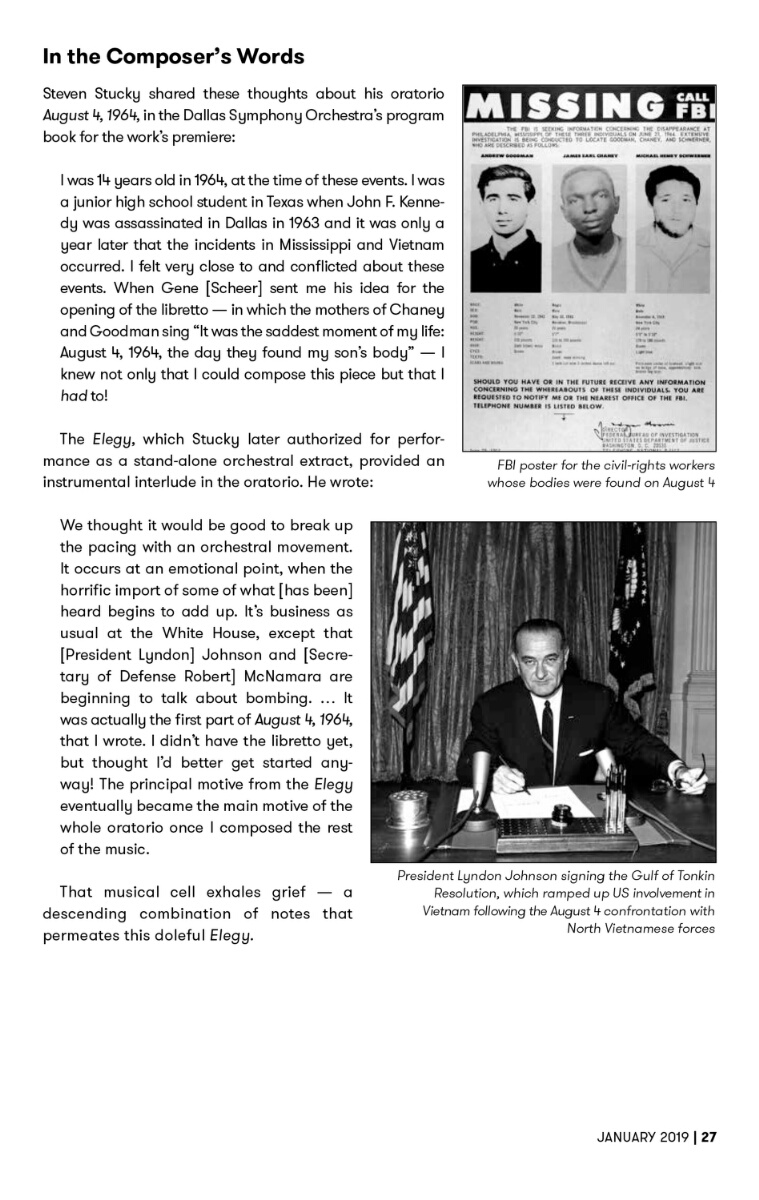

Today, we’re marking the date by taking a closer look at an unusual composition named, quite literally, for this very day 56 years ago. Steven Stucky wrote August 4, 1964 in 2008, on commission from the Dallas Symphony Orchestra. The work premiered in concert under the baton of Maestro Jaap van Zweden – a name that might sound familiar! Stucky’s oratorio follows the events of August 4, 1964, a dramatic 24 hours during the LBJ presidency marked by the Gulf of Tonkin Incident and the discovery of three murdered civil rights workers in Neshoba County, Mississippi. The Elegy, performed in this program presented by the New York Philharmonic in January 2019, provides a haunting instrumental counterpoint to the vocal sections of the oratorio.

Today we remember the great pianist Leon Fleisher who died on Sunday at 92.

Mr. Fleisher made his New York debut with the Philharmonic at Carnegie Hall on November 4, 1944, the first of two nights under the baton of guest conductor Pierre Monteux. New York critics were universal in their praise for the 16-year-old soloist.

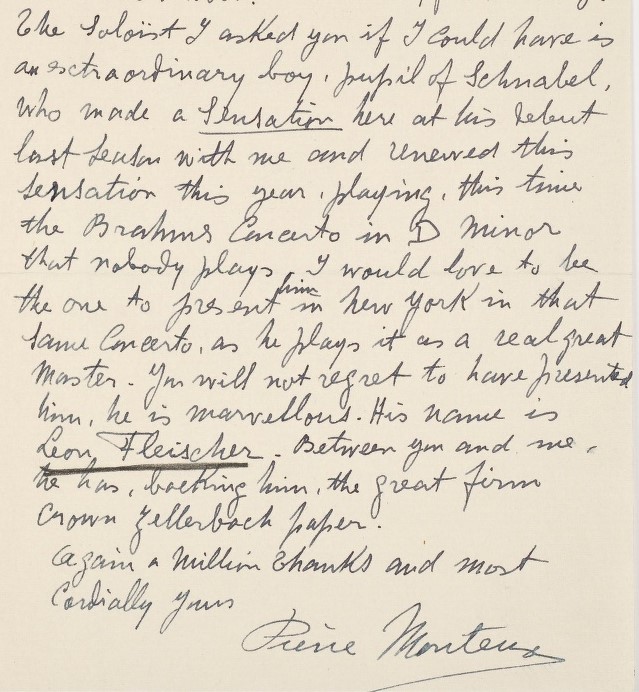

Monteux, then of the San Francisco Symphony, was responsible for bringing the SF-born Fleisher to New York. A series of correspondence between the conductor, Philharmonic Associate Manager Bruno Zirato, and Music Director Artur Rodzinski from earlier that year shows Monteux's deep admiration for the teenaged musician, as well as the sometimes-delicate negotiations around soloists.

In a handwritten letter to Zirato, dated February 19, 1944, M. Monteux writes:

"The soloist I asked you if I could have is an extraordinary boy, pupil of [Artur] Schnabel, who made a sensation here at his debut last season with me and renewed this sensation this year, playing this time the Brahms Concerto in D Minor that nobody plays. I would love to be the one to present him in New York in that same Concerto, as he plays it as a real great master. You will not regret to have presented him, he is marvelous. His name is Leon Fleischer [sic]."

Zirato assented to the request and in a subsequent letter, dated February 29, 1944, Monteux replies:

"In regard to Leon Fleisher I cannot thank you enough. This will please everyone here in San Francisco as we all feel that he is the worthy successor to Menuhin and Stern."